The Story of Mural 44 in Zwedru,

Liberia

Travel in Liberia is such a different

experience when you are in a vehicle with diplomatic plates. Of

course, this was all a new experience for me. In the Peace Corps,

I usually tried to hitch rides on supply transport trucks. I

packed into the back of timber shipments, slept on top of bags of cement

(or at least tried), shivered when it rained, and collected red dust all

over my face when it was dry on those dusty roads. All of these

means of transportation were better than riding in a money bus, a

pick-up truck with a covered frame that held three rows of passengers, a

few chickens, and sometimes a goat or two.

I have to admit, I hated riding in money buses. At six feet, I’m taller than most Liberians. Those extra inches meant I couldn’t sit up straight in the back of the truck. Usually, I hit my head on the roof each time we hit a bump. And, Liberia’s roads have so many bumps once you leave the paved road that stops around Ganta. To get to Zwedru, there was one hundred fifty miles of unpaved discomfort. I was always grateful when someone said, “The Peace Corps man will suffer too much in the back. He needs to sit up front.”

I never turned down that offer.

But, if you travel in a land rover with diplomatic plates, the experience is totally different. There are still bumps that can’t be avoided. However, the whole process is so much more bearable with a seat belt, headroom, legroom, and air-conditioning!

As if that isn’t enough of a perk – and air-conditioning is a HUGE perk – I have to mention the numerous police checkpoints. I wasn’t always as groveling and submissive as I needed to be at checkpoints. Sometimes there could be as many as twenty police stops where I had to get out of the vehicle, show my identification, sometimes open my luggage for inspection, and watch police force bribe money from the driver. It was maddening. But if I wasn’t groveling and submissive, that caused more problems, and in the end, I still had to apologize and then be groveling and submissive.

None of that happened with diplomatic plates. We were waved on without questions. The only other time I had such ease at checkpoints was after a motorcycle accident while in the Peace Corps. I had a gash on my elbow and blood everywhere. No police officer wanted to be responsible for delaying a bleeding white man. It got to the clinic a lot faster than usual.

But, if you travel in a land rover with diplomatic plates, the experience is totally different. There are still bumps that can’t be avoided. However, the whole process is so much more bearable with a seat belt, headroom, legroom, and air-conditioning!

As if that isn’t enough of a perk – and air-conditioning is a HUGE perk – I have to mention the numerous police checkpoints. I wasn’t always as groveling and submissive as I needed to be at checkpoints. Sometimes there could be as many as twenty police stops where I had to get out of the vehicle, show my identification, sometimes open my luggage for inspection, and watch police force bribe money from the driver. It was maddening. But if I wasn’t groveling and submissive, that caused more problems, and in the end, I still had to apologize and then be groveling and submissive.

None of that happened with diplomatic plates. We were waved on without questions. The only other time I had such ease at checkpoints was after a motorcycle accident while in the Peace Corps. I had a gash on my elbow and blood everywhere. No police officer wanted to be responsible for delaying a bleeding white man. It got to the clinic a lot faster than usual.

There was one exception to our treatment

at check points when we crossed the Lofa County line. We had to

wash our hands and get a temperature check as a continued defense

against Ebola. No need to be groveling or submissive or

maddeningly frustrated. I totally understood and agreed with the

precautions.

Even with diplomatic plates and air-conditioning, it was a long ride on unpaved roads to Zwedru. The one hundred fifty mile journey lasted around seven hours. I don’t know how I ever managed it while in the Peace Corps in the back of public transportation vehicles or on top of transport trucks. Well, it was uncomfortable, painful, cold or hot depending on time of day or night, wet or dusty depending on the season, and always, always, very long.

Zwedru was almost unrecognizable. There were some basic buildings I remembered, but there was so much growth. I was unable to find my two previous homes. They used to be in the bush on the outskirts of town. There was no bush or outskirts where they were once located. But, I knew where to find the Multilateral High School. In spite of all the growth, it was easy. And, my friend Joshua had been the principal for ten years.

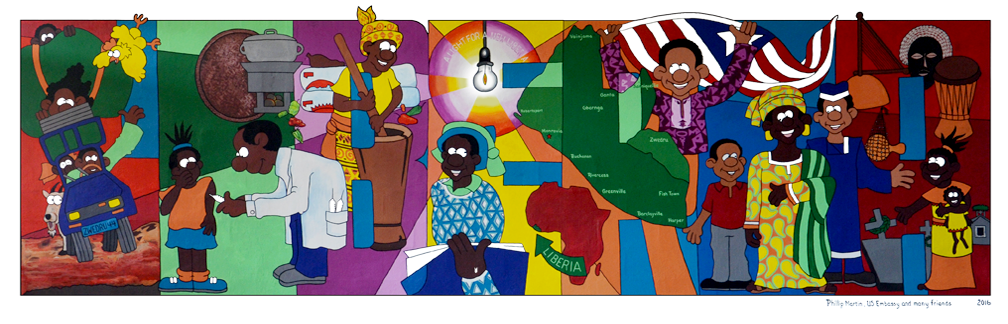

Zorzor was much smaller than Zwedru. My home town had several professional artists and four or five of them were among the twelve to help with the mural project. Upon discussion at our first meeting, we came up with our mural theme. Zwedru was more developed than Zorzor. There was much more electricity and availability to clean water. Their issues of concern included are illustrated left to right on the mural:

Safe Roads. After my trip to Zwedru, I readily agreed with that one.

Even with diplomatic plates and air-conditioning, it was a long ride on unpaved roads to Zwedru. The one hundred fifty mile journey lasted around seven hours. I don’t know how I ever managed it while in the Peace Corps in the back of public transportation vehicles or on top of transport trucks. Well, it was uncomfortable, painful, cold or hot depending on time of day or night, wet or dusty depending on the season, and always, always, very long.

Zwedru was almost unrecognizable. There were some basic buildings I remembered, but there was so much growth. I was unable to find my two previous homes. They used to be in the bush on the outskirts of town. There was no bush or outskirts where they were once located. But, I knew where to find the Multilateral High School. In spite of all the growth, it was easy. And, my friend Joshua had been the principal for ten years.

Zorzor was much smaller than Zwedru. My home town had several professional artists and four or five of them were among the twelve to help with the mural project. Upon discussion at our first meeting, we came up with our mural theme. Zwedru was more developed than Zorzor. There was much more electricity and availability to clean water. Their issues of concern included are illustrated left to right on the mural:

Safe Roads. After my trip to Zwedru, I readily agreed with that one.

Improved

Health Care. I’ve seen enough to know that nobody wants

to get sick enough to need a hospital in the developing world.

Food

Security. In Liberia there is a season called "hunger

season" or "hungry season". It’s the time after harvested crops

run out and before new crops are ready to gather. In Zwedru, the

problem was accentuated when the roads became impassable during the

rainy season. No new supplies could make it to town for two or

three months.

Education.

Okay, I put this in. It’s still the teacher in me. And, I

love maps, so I needed another one of Liberia and Grand Gedeh County.

Traditions.

There is no country cloth made in Grand Gedeh. There are few – if

any – locally made paintings, traditional masks, carvings, or

instruments. Artists in the community hope to change this.

Importance of Family. Nuclear or Extended, Present or Past, family is important in every situation we face in life including civil conflict, Ebola, and hunger season.

The twelve involved in the process liked

the idea of a text that I used to spell “Zorzor”. There was some

discussion that perhaps “Grand Gedeh” was better than using

“Zwedru”. I had my heart set all along on the name of the

town. And, seriously, the name of the county was just too many

letters. So, since these really were concerns across the whole

country, it was decided that we really ought to use “Liberia”.

Everyone agreed.

However, the best idea of the session came from one of the youngest people present. Patrick, an incredible artist in his own right, tied everyone’s ideas together. He suggested that there be a light in the center of the design. It should represent a light shining the way for a new Liberia. I wish it had been my idea, but that was the whole purpose of community discussion for the mural designs.

On the first day of painting, a staff of six or seven really good painters took over once the sketch was completed. I don’t always understand Liberian English, but I heard the artists marvel about how fast I was at drawing my design and how steady my hand was. Yes, I’m always glad to understand those words. But, I had to take everything with a grain of salt. They were also amazed by my desktop mechanical pencil sharpener and the use of a chalk line to make a grid.

In about a half day of work, one third of the color was applied to the mural. Since I had several artists among me, I had them add African patterns to clothing that normally would have been much more solid. And, when I needed an African drum, guitar, and mask, I turned that over to my staff. I just showed an artist where I wanted them drawn. I’d never given up as much control of the murals as I did in Liberia. But, I knew it is the way it should be done when the opportunity presented itself. As it turned out with so many local artists on hand, the mural in Zwedru was the easiest one I’d ever worked on.

Everyone agreed.

However, the best idea of the session came from one of the youngest people present. Patrick, an incredible artist in his own right, tied everyone’s ideas together. He suggested that there be a light in the center of the design. It should represent a light shining the way for a new Liberia. I wish it had been my idea, but that was the whole purpose of community discussion for the mural designs.

On the first day of painting, a staff of six or seven really good painters took over once the sketch was completed. I don’t always understand Liberian English, but I heard the artists marvel about how fast I was at drawing my design and how steady my hand was. Yes, I’m always glad to understand those words. But, I had to take everything with a grain of salt. They were also amazed by my desktop mechanical pencil sharpener and the use of a chalk line to make a grid.

In about a half day of work, one third of the color was applied to the mural. Since I had several artists among me, I had them add African patterns to clothing that normally would have been much more solid. And, when I needed an African drum, guitar, and mask, I turned that over to my staff. I just showed an artist where I wanted them drawn. I’d never given up as much control of the murals as I did in Liberia. But, I knew it is the way it should be done when the opportunity presented itself. As it turned out with so many local artists on hand, the mural in Zwedru was the easiest one I’d ever worked on.

Me with

my artist crew: Koko, Paul, Patrick, and Krah