James Thurber

Your list of Ohio cartoonist might

include Bill Waterson (Calvin and Hobbes), Cathy Guisewite

(Cathy) and Phillip Martin (ah, shucks, I wish I was

on your list). But, long before any of Ohio's current batch of

cartoonists put pencil to paper, humorist James Thurber made

his mark in Columbus, Ohio, and around the world. Thurber, known

for his witty cartoons in The New Yorker magazine, was also an

author, journalist, and playwright. He wrote more than 40 books

including

My World and Welcome To It and the short story The Secret

Life of Walter Mitty. He also wrote seventy-five fables and

numerous humorous essays. In an interview in 1939, Thurber said,

"I'm not an artist. I'm a painstaking writer who doodles for

relaxation."

Truth be told, I have a warm spot in my

heart when I read the works of Thurber. He's one of the few

writers I've ever discovered who has a similar style to me. I can

hear my voice when I read Thurber's words. I like that. I

especially like it since he was also a cartoonist. However, my

artwork looks nothing like his. I was originally inspired by

Charles Schulz and not James Thurber.

Thurber was born in Columbus in

1894. He had a brother, and anyone who has a brother knows about

the foolish things that brothers get into. James Thurber would

probably win in most conversations about crazy antics with your

siblings. He and his brother played a game of William Tell when

James was seven. If you know who William Tell is, you know that

this story has a bow and arrow involved. James, on the wrong end

of the arrow, was shot in the eye. He lost the eye and had vision

problems for the rest of his life. The problems kept him out of

sports and the military, but it allowed him to focus all of his energy

on his very imaginative and creative endeavors.

From 1913 to 1917, he attended The Ohio

State University and rented the house at 77 Jefferson Avenue that in

1984 became the Thurber House

Museum. While at the university, he was the editor of the

student magazine, the Sundial. Unfortunately, Thurber

never graduated from Ohio State. With his vision problems, he was

unable to participate in the required Reserve Officers' Training

Corps. A little too late for Thurber, 34 years after his death, he

was posthumously awarded his long-overdue degree.

After a year in Paris where he worked as

a code clerk for the U.S. Embassy, Thurber returned home to work as a

reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. He eventually also

worked for the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers. The

Tribune sent him back to Paris as a correspondent.

In 1925, Thurber moved to New York City

to work as an editor for the New York Evening Post. Two

years later, he moved on to The New Yorker magazine. He

didn't become known as a cartoonist until after the move to the Big

Apple. It was there, in 1930, that fellow editor, E. B. White

(Yep, the guy who wrote Charlotte's Web) found some of Thurber's

drawings in the trash and submitted them for publication. It must

have been a very lucky Thursday for Thurber, because White only came

into the office one day a week.

Thurber was quite successful with The

New Yorker as an editor from the 1920s to the 1950s. He

drew six covers and many classic illustrations for the magazine.

He drew his cartoons in the usual fashion in the 1920s and 1930s.

But, as his vision worsened, he had to change his method. He drew

on large sheets with a black crayon or on black paper with white

chalk. With the chalk drawings, the photographer needed to reverse

the colors for publication. In 1952, Thurber gave up drawing all

together. He was totally blind the last 26 years of his

life. In spite of his visual problems, Thurber produced more books

after his blindness than before he lost his sight.

In October, 1961, Thurber had a blood

clot on the brain. He underwent surgery and drifted in and out of

consciousness. He held on for almost a month, but his doctors said

that he had several small strokes and hardening of the arteries.

He passed away on November 2 at the age of 66.

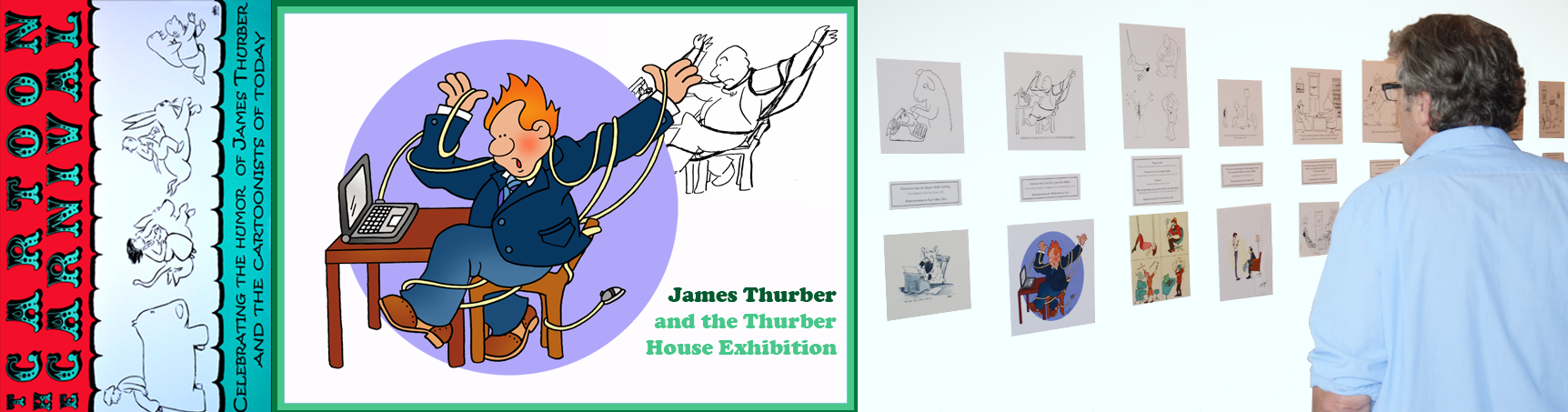

In celebration of the 30th anniversary

of the Thurber House Museum in Columbus, more than twenty local Columbus

cartoonists were invited to make their own renderings of Thurber

cartoons in their own style. And, I was included in this

group! There were no rules. Imaginations were free to run

wild, and that is exactly what happened. The exhibition, hosted by

the Wild Goose Gallery, was then planned

to move to Jefferson Avenue for permanent exhibition.

In my particular drawing, I selected

Thurber's American Male Tied Up in a Typewriter Ribbon. If

you are too young to fully understand the frustration of that moment,

consider yourself a blessed member of a computer society. I

updated the art to the computer age and wrapped the American Male up in

a computer mouse cord. But, it was my intention to keep a very

true element of Thurber's drawing in my version. I tired to match

every curve and twist of the typewriter ribbon with my mouse cord.

Each generation has their own problems and frustration with

communication. But, I promise you, a mouse cord is a whole lot

less messy!

My piece of art exhibited for the 30th

Anniversary of the Thurber House Museum in Columbus.